Polish-Egyptian Archaeological and Conservation Expedition to Kom el-Dikka

البعثة البولندية-المصرية للحفائر الأثرية وأعمال الصيانة بكوم الدكة الاسكندرية

The site

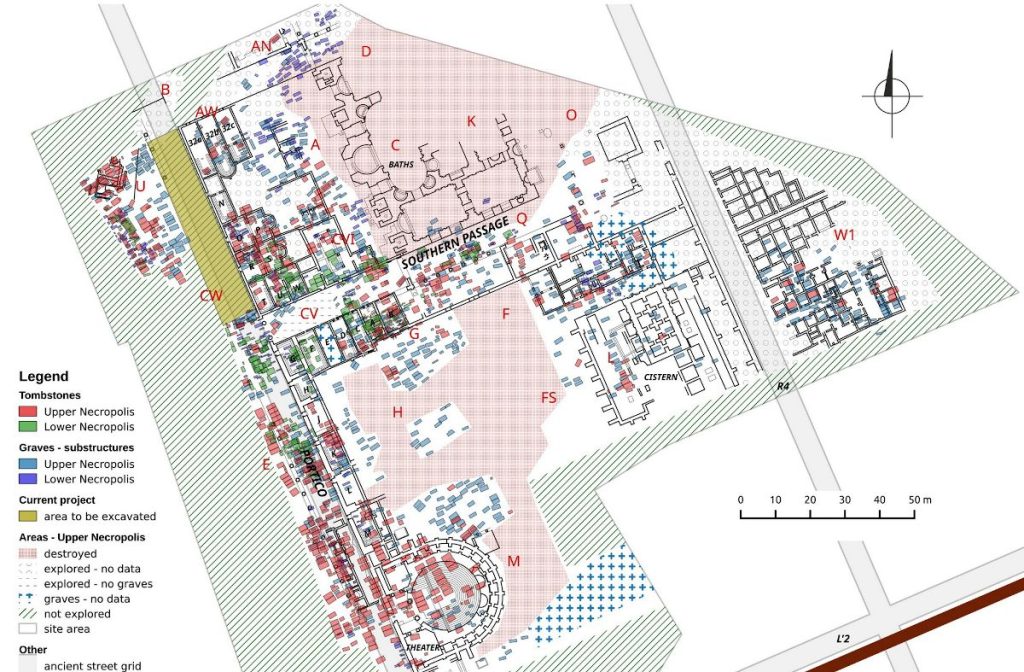

The archaeological site of Kom el-Dikka has been studied since 1960 by Polish researchers from the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology of the University of Warsaw. When the Polish Team began excavating there on the initiative of Professor Kazimierz Michałowski, the work focused on Roman layers. However, the buildings of what was later identified as a civic centre of

Late Roman Alexandria were covered by an early Islamic necropolis which prevented easy access to earlier remains. Some of the grave pits of the so-called Lower Necropolis cut through the remains of the Late Antique buildings. More than half a century of meticulous archaeological work at the site has resulted in a huge amount of data and numerous artefacts covering all layers, including the

early Islamic necropolis. The material from Kom el-Dikka gives us a unique opportunity to investigate the Muslim Mediaeval community of one of the most important cities in Egypt. By exploring a new area of the cemetery, we could acquire new data that would be sufficient to supplement the materials already

available for study to an extent justifying the use of different methods that are not compatible with what has been done before.

Mahler, based on archaeological site plan, PCMA UW | W. Kołątaj, A. Pisarzewski, G. Majcherek,

D. Tarara

Work on the Muslim necropolis in spring 2024

Excavations

Archaeological excavations in the Mediaeval cemetery at Kom el-Dikka site were carried out between March and June 2024. The results of the research conducted so far (for the most recent and comprehensive study of the Mediaeval cemetery at Kom el-Dikka see Mahler 2021) indicate that the upper layer of this cemetery was most probably used during the Fatimid period, while the lower layer was used between the beginning of the 9th and the mid-10th century CE. The graves of this necropolis overlie the remains of the Late Roman complex of public buildings, which included numerous lecture halls (of which the so-called Theatre was the biggest), baths, and the monumental cisterns that supplied the baths with water.

The original function of these public buildings was already forgotten when the necropolis began to be built in this place and graves were dug into the structures which were barely visible on the surface.

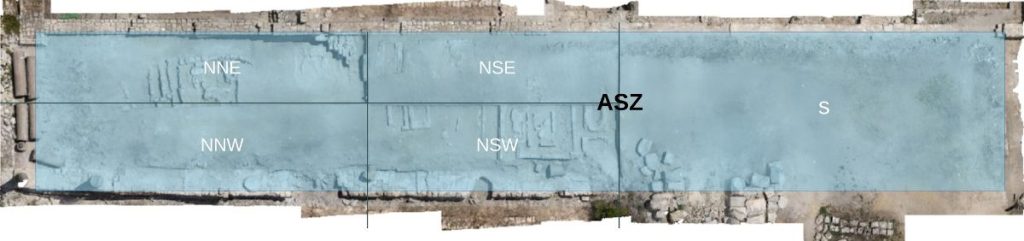

The current excavations in the necropolis are being carried out in the area of the so-called Theatre Portico, north of the intersection with the Portico of the Baths running perpendicular to it, in the previously unexcavated part. Within the archaeological division of the site, the area of excavations is located between Sectors AS, AW, CW to the east; Sector U to the west; Sector B to the north; and Sector CV to the south. The exact location can be seen on the plan [Fig. 1]. The entire area, encompassing approximately 550 square metres, is nearly 58 metres long and more than 9.5 metres wide. It has been designated as Sector ASZ and divided into eight sub-areas to facilitate documentation during exploration. These sub-areas were delineated in two stages. First, the entire

area was divided into two parts, N and S, by a line perpendicular to the long axis of the portico, and these two parts were then divided into four quarters each: NW, NE, SW, and SE [Fig. 2].

As a result, the full reference to one of the smallest parts within the Kom el-Dikka archaeological site would always consist of six letters (e.g. ‘ASZ NNE’).

Before excavation could begin, the limestone blocks and granite column shaft fragments covering most of the area under investigation had to be moved. The architectural stone elements that were blocking the way came from excavations at nearby sites and were brought to the Kom el-Dikka site for storage. Finally large blocks of limestone that were preventing the excavations were taken to

storage in Marea. The whole area was then cleaned of vegetation. Excavations began in the NNE quarter, followed by the NSW, NSE, and NNW quarters. The order and pace of the work was systematically adjusted to maximize the visibility of the objects uncovered and to facilitate the data collection process.

In the northern part of the area, NNE and NNW, we found no remains of grave superstructures apart from a few fragments of unplastered stone frames in the NNW area. In the NSW and NSE areas, we found numerous superstructures but the level of the associated grave boxes has yet to be excavated.

Necropolis

During the excavations we uncovered 24 grave superstructures (tombstones) [Fig. 3] and 16 substructures (grave boxes). Some of the burials, 31 in all, were simple pit graves, but the overwhelming majority of the hundred or so individuals identified so far were buried in grave boxes made of stone, each of which contained several inhumations.

R. Mahler)

The superstructures were of a wide variety of forms, some with the remains of elaborate stucco stepped ornamentation outlining mihrab-like and geometric patterns. The superstructures were placed directly on the ground without foundations or on top of earlier tombstones. They were constructed of small limestone blocks used for the frame and small fired bricks used mainly for the

stepped ornamentation, which was elaborately finished in plaster [Fig. 4].

The poor state of preservation of the skeletons was to be expected from the long experience of other areas of the cemetery. However, whereas in the case of the Upper Necropolis the graves had previously been heavily commingled, with all the skeletons swept aside, the skeleton of the last individual buried in a grave might have been undisturbed. However, in the NNE area most of the

inhumations were preserved in their anatomical arrangement.

So far three main attempts have been made to date the necropolis and divide it into phases. The identification of chronological phases that could be generalized to the site as a whole is not easy at Kom el-Dikka due to the uneven distribution of graves and local differences in their density, forms, and vertical relationships. The area currently under investigation seems to be no different in this respect. In the NNE quarter, contrary to our expectations, there are so far no graves that can be identified with certainty as belonging to the Lower Necropolis phase. Although the stone blocks forming two of the grave boxes from this area resemble Lower Necropolis structures known from

other parts of the cemetery, the placement of these substructures between the graves of the Upper Necropolis casts considerable doubt about their early chronology. The best category of finds known from the necropolis at Kom el-Dikka which can be used to establish the chronology of burials are grave stelae. The inscriptions on them can either provide precise dates or the time of their creation can be deduced palaeographically. The chronological division of the necropolis recently proposed (Mahler 2021) is based almost exclusively on the dates acquired from the inscribed stelae. So far however, no finds belonging to this category have been found in Sector ASZ. The lower horizon for the establishment of graves in this area has only been confirmed by a single coin [Fig. 5] provisionally dated to the Sasanian invasion thus giving a relatively early terminus post quem. The upper horizon up to the end of the 12th century CE is corroborated by the ceramics of the 13th–14th century CE discovered in the layers covering the graves. The problem of these relatively late ceramics needs to be investigated further because it is not clear whether the layers yielding it are contemporaneous with the latest graves or whether its

presence is the result of earlier excavations.

Anthropological analysis

When investigating ancient cemeteries, the bones and teeth of the inhumed provide invaluable evidence for the study of the living, both from a biological and cultural point of view. Such studies, however, require large amounts of data and their collection is very time consuming.

The process of analysing human bone remains was divided into two general stages. First, each skeleton was carefully exposed in situ to allow for photographs to be taken and drawings and descriptions done. At the same time, all osteological measurements feasible were taken in situ. This in order to collect as much data as possible as the often severe degradation and fragmentation of the bones would most likely prevent the collection of most of these measurements after the bones had been moved to the laboratory. The second phase consisted of a full examination of the burial and the transfer of the skeletons to the field laboratory where they were cleaned and analysed. The skeletons were carefully examined one by one under the supervision of bioarchaeologists to reduce commingling and further fragmentation of poorly preserved bones. These were examined in detail in an on-site field laboratory according to established standards for the macroscopic analysis of human skeletal remains. This was done in the hope of improving our understanding of the biological characteristics of the populations who buried their dead at the site in the early Islamic period. Although more than 2.5 thousand individuals have been analysed so far, there is still relatively little data that can be used in the analyses due to the severe fragmentation and erosion of human bones from the cemetery at Kom el-Dikka.

Whenever possible, the commingled assemblages under analysis were sorted into individuals. The minimum number of individuals analysed so far is 81 but the total number of individuals discovered can be roughly estimated at one hundred. Of these, 20 were female and 16 were male. However, there were three highly uncertain sex determinations in each of these two groups. Sex determination was not possible for 45 of the inhumations. In the majority of these cases (41), the condition that made such a determination impossible using morphological methods alone was the low age-at- death. The remainder are awaiting a full examination. The documentation produced followed generally accepted standards and included, in addition to measurements taken both in situ and in the laboratory, macroscopic descriptions of the morphological features and observations of the dentition. For the methodological approach, see e.g.:

Efthymia Nikita (2017), Richard H. Steckel, Clark S. Larsen, Paul W. Sciulli & Philip L. Walker

(2006), Tim D. White (2000), and Jane Buikstra & Douglas H. Ubelaker (1994).

References

Buikstra, J., and D. H. Ubelaker, eds. 1994. Standards for Data Collection from Human Skeletal Remains. Arkansas Archeological Survey Research Series No. 44 44. Fayetteville, AR: Arkansas Archeological Survey.

Mahler, Robert. 2021. Changing Life in Egyptian Alexandria: The Testimony of the Islamic Cemetery on Kom El-Dikka. Peeters. https://doi.org/10.2143/9789042945432.

Nikita, Efthymia. 2017. Osteoarchaeology: A Guide to the Macroscopic Study of Human Skeletal Remains. Academic Press.

Steckel, Richard H., C. Larsen, P. W. Sciulli, and P. L. Walker. 2006. ‘The Global History of Health Project. Data Collection Codebook.’

White, Tim D. 2000. Human Osteology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Here you will only find information concerning our work within the scope of the ‘Muslim women in Fatimid Alexandria…’ project. For more about Kom el-Dikka archaeological site and our work there, see the expedition summary on the PCMA website